>oiktozian: Oğuz Tutal

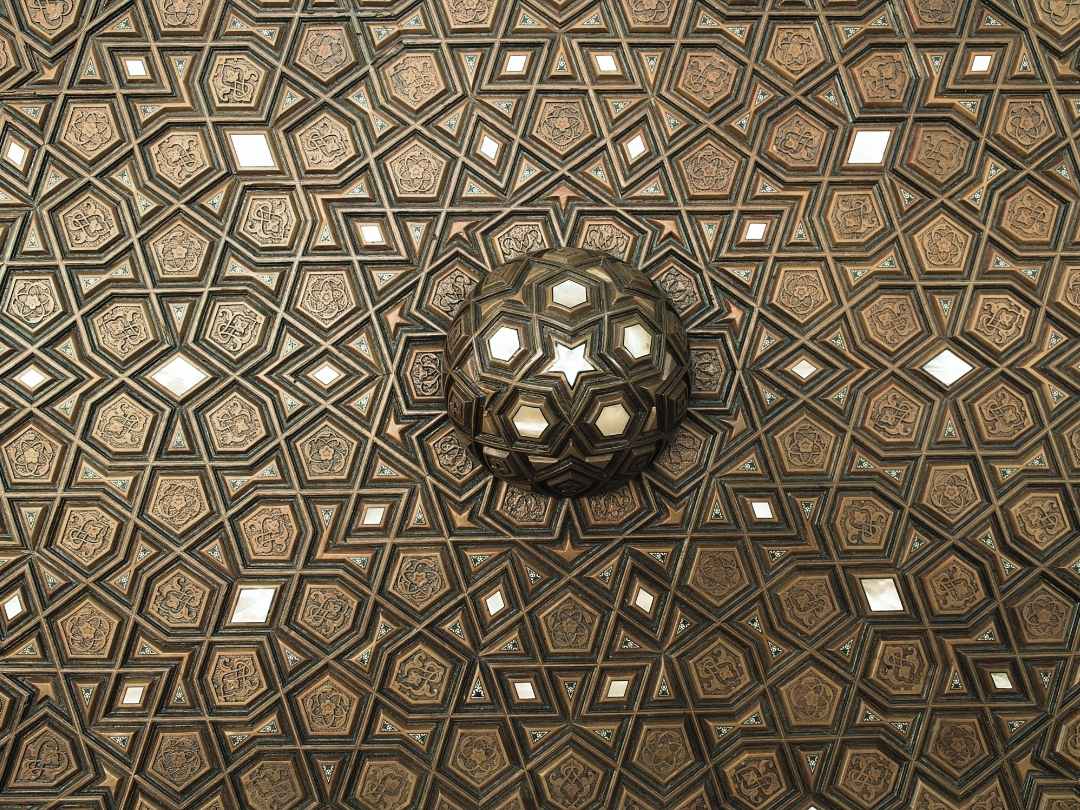

Title of The Work: Systems Die as Well as Ideas

Original Title: Düşüncelerin Yanısıra Sistemler de Ölürler

In addition to people, animals and ideas, systems also die. Then new ones come along and fill the void left by the previous one. When someone or something kills someone or something, the blame tends to fall on the weakest and easiest to bite. It is easier to blame a politician, a terrorist, a disease, a weapon. However, the truths that are known to everyone, but not spoken by anyone, are kept secret like a secret, and it is hesitated to talk about them in public. One of these truths is that systems are the most deadly, fragile and threatening instruments.

Such an economic system dies at regular intervals, or is kept alive on life support, then undergoes a soul transmigration and is reborn. These changes, however, have painful consequences. The death of economic systems means the death of the people within that system. The death of those people means the death of women, men, old people, children, black and white people, each with a different story.

Like many other states and empires throughout history, the death of the economic system of the Ottoman State/Empire was long and painful. Starting from the 17th century and ending in the 20th century, the process brought many pains and losses. So, can we ask why an economic system collapsed as we ask why a handkerchief bleeds? If we do, what answer will we get? What do we come across?

I will now trace the trail of death by analysing the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in particular.

Starting in the 17th century, the price revolution, the inflation problem, the deterioration of the fief system and the industrial revolution initiated by Europe led to the emergence of important problems. The Geographical Discoveries, which coincided with the same dates, and the diversion of trade routes away from the Ottoman geography and the wars that resulted in continuous defeats weakened the authority of the central administration. As the central administration structure, which was the source of the Ottoman power, weakened, different actors in remote provinces and rural areas gained importance, which accelerated the emergence of the iltizam system with the strengthening of the ayas. Due to the cultural characteristics of Ottoman society, its military power and the great threats that did not exist in the neighbouring geographies, a structure similar to the feudal order in Europe did not and could not emerge in Anatolia. This prevented the ayan class and local actors from gaining power against the central authority. But the system was moribund and once the cancerous cell started to spread, it was very difficult to prevent it.

There were many events that battered the sick man. Foremost among them was the Governor of Egypt, Kavalalı Mehmet Ali Pasha, who shaped the economic and administrative system of Egypt in the way he wished. When Mehmet Ali Pasha was about to reach Kütahya and put a dagger in the heart of the man, he was surviving with the help of Europeans who wanted the patient to live. The patient had to live so that the Russian threat could be eliminated and economic and commercial interests could be maintained through co-operation. The Ottoman Empire was a reasonable target due to its geographical proximity, being a large market and its substantial non-Muslim population. At the same time, once the deaths started, the epidemic could gallop across the fertile lands of Europe.

The central budget, overwhelmed by problems such as the continuation of military and political reforms, increasing palace expenditures, and paying the salaries of bureaucrats, had to seek external loans. External borrowing reached critical levels after a while and in the World Economic Depression of 1873, it became impossible to borrow from abroad. The repayment of debts was unilaterally stopped by the sick man. After protracted negotiations, it was decided to establish Duyun-u Umumiye. Duyun-u Umumiye started to work as an institution established within the country to collect the debts of European states and to collect taxes on behalf of western states. This organisation, which seemed to be beneficial for both sides at first, grew uncontrollably after a while and became in a position to collect one third of the taxes collected by the Ottoman Empire. In addition to the tax and trade privileges granted to foreigners by the Treaty of Baltalimani, which is only mentioned in history books, the Edict of Reform signed in 1856, the Law of Land signed in 1858 and the contract signed in 1867 paved the way for foreigners to invest in the country, for the sale of land by persons other than the state and for foreigners to buy land in the empire. Taking advantage of the opportunity, countries distributed passports of their own countries to foreigners in the Ottoman Empire, thus creating a non-Muslim bourgeoisie class that gained privileges. This class was concentrated in port cities such as Istanbul, Izmir and Thessaloniki, enjoying living conditions ahead of their time and developing new investments and trade channels with the advantages of these cities such as transport and infrastructure. This ethnic and religious segregation started in a way that would lead to significant problems in the future, and its effects continue to this day. Later on, this situation would lead to the deportation of the Armenian population in 1915 and the migration of the Greeks more than once as a result of exchange.

In such a situation, at an unknown time, the clock stopped and the Ottoman Economic System left us. It left behind migration, war, hunger, class conflict, disease and millions of deaths as a result. These developments, the causes of which can be debated at length, are the unchangeable rule of the fact that one must live to die.

A state is dead. Just like everything else whose path passes through death.