oiktoz interviews; is a multi-layered narrative series extending from theater to literature, from the world of TV series and cinema to the backstage. In these interviews; we come together with all the actors of the performing arts and the world of narrative such as actors, writers, directors, stages, venues, stage designers and critics.

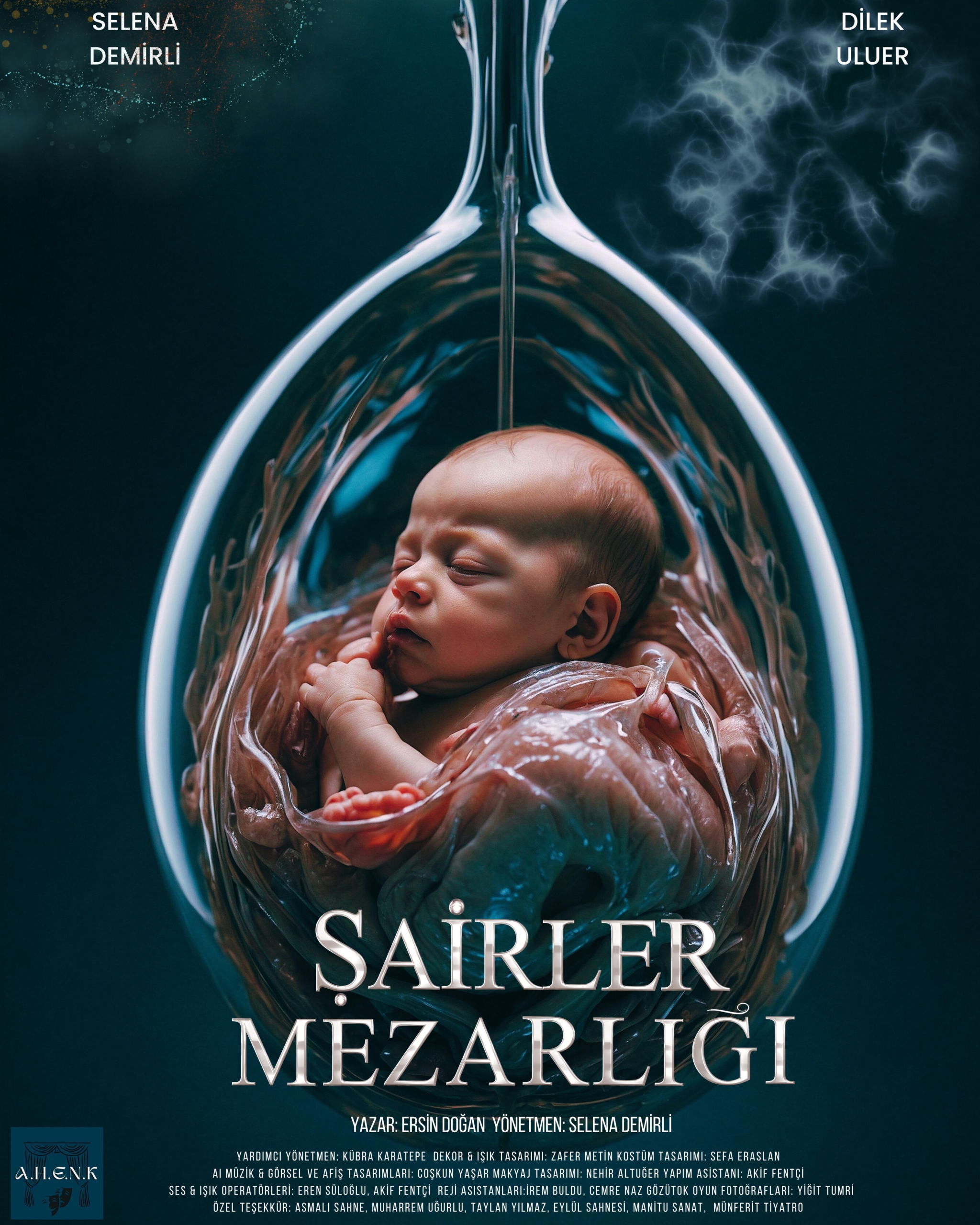

In this episode, we had an in-depth interview with A.H.E.N.K Theater founders Selena Demirli and Ersin Doğan on stage, literature, poetry and existence, specifically for the play “Poets’ Cemetery” (Original Name: Şairler Mezarlığı).

Poets’ Cemetery; touches upon the encounter of an unborn soul and a poet in the afterlife and the boundaries of being human.

You can either read our written interview or watch our video interview at the end of the page to witness the magic of independent theater, the creative process and the inner struggle.

___

Hello Ms. Selena and Mr. Ersin. Today we will be chatting about the theater play “Poets’ Cemetery”.

Before we move on to our questions specific to the game, we would like to start by getting to know you a little bit.

Selena Demirli:

My name is Selena Demirli, I am 26 years old. We are the producers of A.H.E.N.K Theater, which we founded with Ersin, and our play called Şairler Mezarlığı. I am also a director and actor in the play. I graduated from Bahçeşehir University Conservatory, Department of Acting. I completed my undergraduate education in Turkish Language and Literature. I received three years of preliminary training at Darülbedayi Workshop within İstanbul City Theatres.

I was born in İzmir and started my theatre life in İzmir when I was a child. After deciding that I wanted to do this as a profession, I moved to İstanbul. I have been working as both a director and an actor in various private theatres for a long time. However, this time, we brought to life a project that was completely our own production. Ersin and I founded A.H.E.N.K Theater while searching for an answer to the question of “How can we build a freer space?” We started staging Şairler Mezarlığı together with our companions.

Ersin Doğan:

I am Ersin Doğan, 34 years old. I stepped into the world of literature, especially literature, as a novelist. I used to write stories before, but my first printed book was my novel Uyanma Vakti, published in 2021. My second novel, Mahrumiyet Oteli, met with readers in 2023.

After my marriage to Selena, I got more involved in the world of theater through her. I had been watching theater plays for a long time and analyzing them from a writer’s perspective. I had an internal evaluation process regarding play texts with thoughts like “This scene could have been like this, this structure could have progressed differently.” This process led me to write play texts. My first theater text emerged when a story of mine was adapted for the stage. I have written a total of eight plays to date; Şairler Mezarlığı is one of them. I wrote it about 1.5 – 2 years ago.

In addition to theater and literature, I also have an engineering background. I am a mechanical engineer and graduated from Karadeniz Technical University in 2014. I have had many different experiences, from the political atmosphere of Ankara, the city I was born in, to the nature of the Black Sea, to doing my military service as a commander at a border post for a year. When I added my experiences abroad, this diversity seriously nourished my writing skills.

Finally, we came to the idea of establishing our own theater. Because when you write a work, it is very unlikely to send it to someone and expect it to be evaluated. This is unfortunately a reality for many writers. You can hear stories like “I sent this project to 80 people, it happened in the 81st” or “Nobody valued it, I decided to do it myself and it was successful” from many artists. The Poets’ Cemetery was also the product of such a process for us. We were actually working on another play; but this text suddenly emerged. I always describe this play as ‘a world where truths come together’. Thus began our journey to the stage.

First of all, can you tell us a little about the play “Poets’ Cemetery” for those who will watch it for the first time?

Selena Demirli:

Of course, with pleasure. When you first examine the play through the eyes of the director or a spectator, its name and the presence of the poetic element naturally raise the question: “Is this a poetic play? Do the characters speak in poems?” Even the name of the play carries many question marks. In this respect, I agree.

To briefly mention its subject – and Ersin will explain the background of the play in more detail – the play takes place in a world unknown to us, namely the “other world”. In this dimension, which is believed to exist after death, we witness the encounter of two different souls. One of these souls is a premature baby who was lost on the threshold of life, born at 7 months, and who could only live in the world for 8 hours; in other words, a being who was not born healthy and was thought to have special needs. The other is a real poet, a woman named Piraye, who lived a life intertwined with poetry.

The two come together in this place called “Poets’ Cemetery” because both of them state that they are poets. Of course, the character of Mısra here is not actually a poet; however, during the 33 weeks she spent in her mother’s womb, she grew up in a world full of poetry. She was given the name “Mısra” because of her mother and father’s love for poetry. Mısra also says her name and identity in this way in the afterlife. Spirits are classified according to their professions here, and the first ‘poet’ spirit we encounter is Mısra.

Ersin will explain the reason for this choice, in other words, why a single spirit is represented here, in more detail in a moment. Because this is a question we are frequently asked. As I read the text, as our conversations progressed, I understood the literary criticism behind this structure better, and my interest in the text deepened.

The play progresses with the encounter of these two spirits, Mısra and Piraye; their pasts, literary queries, the boundaries of poetry and their meaning. Over time, the play area turns into an experimental research field where we observe their bodies and spirits in the form of poetry. In short, the relationship between two souls in the afterlife through poetry and the gradual evolution of this relationship into a ground of conflict constitute the main axis that forms Poets’ Cemetery. A world of poetry, a field of existence, a fiction that explores the possibility of poetry becoming flesh…

Ersin Doğan:

Yes, telling about Poets’ Cemetery has always been a complicated feeling for me. In our conversations about art and literature, I would always say, “One day I will make a film, but no one will watch it.” This would be met with a smile by people, but I think this sentence is quite consistent with the reality of society.

When I look back today, Poets’ Cemetery was actually exactly such a project. It was a difficult project, very difficult in fact. We wanted to bring together two fields that do not get the value they deserve in Türkiye and the world – theater and poetry – and present them to the audience. That’s why Poets’ Cemetery became a symbol of resistance for me. As Selena mentioned earlier, there is a frequently asked question: “Why is there only one person?” We can go into the details of this in a moment, but this choice is part of the critique at the center of the text.

From my perspective, this play is a writer’s protest. Many people who saw my poems on social media asked why I hadn’t published a book of poems. Some said, “Your poems are more impressive than your novels, why don’t you publish them?” But in Türkiye, the number of publishing houses that want to publish poetry books is quite low. In fact, let alone publishing houses, poetry files are often thrown away without being evaluated at all.

In such an environment, poets in Türkiye do not have books, but only cemeteries. And those cemeteries contain at most one person. I set out with this idea. I have written many stories and two novels so far; I have started a third novel. However, I have never named any of my works during the writing process. I would always name them after the work was finished. However, Poets’ Cemetery was a first in this sense. The protest inside me told me from the very beginning: “This work should be called Poets’ Cemetery.” And I created the text based on this title. The characters, events, and plot took shape after this title. The process began like this…

Many artistic productions actually emerge as a matter of concern. Art is a powerful tool to express a concern. What was your concern when you created this game?

Ersin Doğan:

The basics of the work actually start like this. Yes, we came up with the name Poets’ Cemetery from the very beginning. But I always say this: Before Poets’ Cemetery came into being, some of my actor friends or people involved in this business would come to me from time to time and ask, “I have a project in mind. You also write a novel, can you write this idea?” My answer was always clear: “No, I can’t.” Because it’s your project. You’ve already written that story in your mind. All you have to do is put it on paper. If I write something about that idea, it becomes my project and something completely different from yours will emerge. Because it will be a text written by Ersin Doğan. In other words, everything should have a language and spirit in Ersin’s language.

Poets’ Cemetery also started from such a place. First, the name was chosen. Then the character of Mısra came into the picture, and then Nazım’s Piraye came into the picture. Mısra’s troubles and Piraye’s troubles began to clash. Thus, a story was born that carried the struggle of man with man to an area independent of this world.

This area may change according to the person’s belief: If you believe, you can call it the “afterlife”, if you don’t, you can call it the “other world”, “parallel universe”, “a dark consciousness”, or even “a point in space”. Whatever you call it, the issue is actually the same: The struggle of man with man.

When I shared this play, I always said:

“We set out to tell the struggle of man with man by throwing poems.”

Yes, Poets’ Cemetery initially started as a writer’s protest. However, it exceeded these boundaries in the process. There are still traces of this criticism in the play, but the issue is not only this. We basically established such a structure that we brought the struggle of man with man, his effort to heal with poetry, and his attempts to understand and question each other to the stage. We tried to express many characteristics that exist or do not exist in human nature with this play. We wanted to share all these feelings and conflicts with the audience.

At this point, I would like to emphasize Selena’s directorial vision. It was not an easy task to bring a profound text like The Poets’ Cemetery to the stage and make it transferable to the audience. But thanks to the original, colorful world she created, the text became watchable and felt. This was very valuable.

In short, our concern was the struggle of man with man. We preferred to tell this through the conflict of two poets. But the play has a rich structure that includes not only poets, but many more; many different people, characters and ideas.

What kind of preparation process did you go through while preparing the play for the stage, what inspired you?

Selena Demirli:

This process was really quite painful and difficult. Last May, we said, “Yes, we will now build a creative space and we will do it with our own means.” Frankly, I did not have the courage at the beginning of this process. Ersin had another text and I was going to take part in that play. That text still excites me, I still eagerly await its staging.

However, the process of bringing Şairler Mezarlığı to the stage began with my play partner Dilek Uluer’s deep belief and excitement in this project. When I shared the text with her for the purpose of exchanging ideas, the interest she showed motivated me as well. Because this text offered me the opportunity to combine my connection with literature with my passion for theater as a graduate of Turkish Language and Literature. But beyond that, it required a very strong design language. It was necessary to create a universe far from the reality of this world. In my opinion, the only being that belonged to this world was Piraye — a character who carried all the human burdens as a woman, a mother and a poet.

However, Mısra did not belong to this world. A soul that came into the world when it was 7 months old and lived a life of a few hours… It did not live to say, “I did not breathe to become a human being.” Therefore, an extraordinary, unconventional design was needed to bring this character to the stage. This required great courage. Both directing and acting was a great challenge for me.

At this point, Dilek’s motivation and the contribution of our valuable companions were very valuable. Our assistant director Kübra Karatepe, our production assistant Akif Bahtiyar Fentçi, our assistants Cemre Naz Gözütok and İrem Buldu, Zafer Metin in set and lighting design, Coşkun Yaşar, Eren Süloğlu and Mehmet Ay in music, Sefa Eraslan from the technical team, our costume designer… The support and aesthetic approaches of all of them throughout the process made me feel very comfortable.

Then I asked myself the following question: “Selena, make a choice. What will you focus on when staging this powerful text?” And I found the answer in poetry.

Poetry is a very flexible field of expression; There is music, dance, rhythm and contrast in it. It can have opposite meanings at the same time and this contrast can give rise to new meanings. Therefore, I constructed this text like a poem. I wanted the play to take on a poetic form.

I also aimed for the two characters to represent two different poems with their body languages:

Piraye is like a solid, hard and cold poem; Mısra is a fluid, watery, free poem… One is ice, the other is water. One carries the deep wounds of a person, the other is a being that has never been experienced yet but has been kneaded with poetry from birth. Body language was very important here. I worked intensively on the physical flexibility of the character Mısra in particular. Because babies use their bodies differently; they move their fingers and feet freely. I was very impressed by a detailed ultrasound image shared by an obstetrician. I watched how a 33-week-old baby moves in the womb and what it feels many times. Especially the examination of the uterus with the thumb, the flexible movements of the fingers… I directly apply these movements in the cradle scene at the beginning of the play.

As for the design… Our music gained an abstract structure that does not belong to this world with Coşkun Yaşar’s artificial intelligence-supported production. In the lighting and set design, a cradle was placed on the stage with Zafer Metin’s suggestion. We wanted this cradle to represent the womb. At first, I told Ersin, “It takes courage to use this cradle, will we fall off the swing?” but it was very effective in the end. This distinction continued in the costume design: Mısra’s color is anthracite – a tone related to the past, death, and being in the shadows. Piraye, on the other hand, is pure white; with all the nakedness, purity and wounds of a person…

The greatest source of inspiration for me was poetry. I created this play as the struggle for existence of two different poems and their conflict with each other. I set out with the question, “If this play were a poem, what kind of poem would it be?” My answer was this:

Two opposing poems touching each other in the end, creating a new poem and a new birth.

And the Poets’ Cemetery is exactly that: a universe of poetry.

You both directed and acted in the play. One body has to be two different people. How did you manage this process and two separate egos? Also, did you ever clash with the author about the text?

Selena Demirli:

This is a really good question, thank you. I want to talk about this text in particular. Because this text already contains a big change in itself. Interfering with the text, touching that poetic universe created by the author, would not be the right approach in my opinion. Because this text is a poem and what we call poetry is a subjective area; it has different meanings for each receiver.

Ersin Doğan, as a writer of this text, has reduced almost all the dialogues to poetic form. In most scenes during rehearsals, we perceived these dialogues like Shakespeare sonnets. We worked without changing a word because even one word really had a big meaning.

You feel this very clearly. For example, there is a sentence in the text that says:

“I feel the sadness of wandering the flowery streets without me.”

There are many layers in this line. With the expression “wandering without me”, is the character of the line only watching these streets from a distance because he cannot make his own soul belong to a physical being? Or does she address Piraye, the mother figure, or all people like this: “Did you always walk the flowery streets without me?” There are so many layers of meaning in this single sentence that you can’t even touch the syllables, not just the words.

Every sentence in the text is so dense and multi-layered. That’s why Ersin and I had no conflict. I said, “We are taking this text as it is and bringing it to the stage.” Because understanding it, even internalizing it, required a great deal of effort.

In terms of directing, I especially preferred to be closed to external voices. Normally, I like to listen to and discuss different ideas, but this text was so original and deep for me that I wanted to protect it from external factors. At the same time, this text was a building block that developed my academic eye and expanded my vision of directing. Dilek Uluer was very respectful in this regard, she implemented whatever I said. Kübra Karatepe and all my assistant friends also provided great support.

In terms of directing, I tried to create my own world. Because in this text, which has a poetic integrity, every different interpretation coming from outside could disrupt the harmony in the whole structure. That’s why I left the design area a little more free. Especially in the lighting design, the shadow element was very valuable to me. Shadow is a powerful narrative tool used in many theater plays today, but in the case of Şairler Mezarlığı, shadow represented incompleteness, regrets, and unfinished lives. It also presented a visuality that represented the similarity of Mısra and Piraye and their common destiny.

Now, coming to the acting part…

It was quite challenging. It required physical preparation, flexibility, and conditioning. I worked on the flexibility of the toes, especially for the character of Mısra. Every word had to reach the audience correctly in terms of diction and phonetics. Because yes, the audience will perceive the text with their own interpretation, but there had to be an essence that we wanted to convey. The audience should be able to say: “There is another meaning in this sentence.”

Therefore, there is no room for human ego here. We had to do a pure, correct, and consistent job. We progressed together, as a team, by clearly sharing the tasks and without anyone interfering with anyone else’s work. Working with a true collective consciousness, we tried to reach a poem in the whole play.

Ersin Doğan:

Perhaps we should add this here. People usually wonder: “Will there be a conflict between the writer and the director or the actors? Will something be removed from the text?”

As a writer, I am of course not against some interventions if it will contribute to the text. In fact, I have another play to be staged this season, and I am showing the same approach there. But the situation was different in the case of Şairler Mezarlığı. This text had a chain structure. If you removed a sentence from one section, the connection with another scene that would come in the future was broken. Therefore, the team was aware of this sensitivity without me having to say anything. They made an effort to preserve that integrity from the very beginning.

When you were creating Mısra and Piraye, did you add anything from yourself or Ms. Selena, or did you create a completely independent imaginary character?

Ersin Doğan:

To be frank, I have never written a play with a character in mind. But when I write, the following process happens in my mind: The writer is actually a director in his own world. When I write, I stage the characters in my mind. I visualize many details in my inner world, such as who will play, what kind of direction will proceed, which emotion should rise in which scene. That play is already staged in my own mind. Then, during the actual staging process of the play, I think, “I wonder how the director interpreted the world I created in my mind?” The question, “What did he take from the world I created, what did he make different?” is always on my mind.

If I talk specifically about Dilek, we did not know her when she was writing the Poets’ Cemetery. We met later. One day, we went to see the play called Sustuğumuz Yerden Yarayız, where Dilek was performing. We had the chance to meet after the play. We ran into each other again at an awards ceremony afterwards and had the chance to chat.

The interesting thing is: Selena sent the text to Dilek without my knowledge. Dilek was very impressed when she read it because she realized that there were serious similarities between what was told in the play and her own life story. Dilek told us this later. That’s why this text touched her very much.

I always remember this situation. I usually wait outside instead of watching the play. But one time I was at the edge of the stage. After Selena made her opening speech behind the curtain and took her place, she came before Dilek entered the stage and was crying at that moment. This was very striking to me. Dilek had established a strong connection between what Mısra told her and her own life and had gone on stage with that feeling. Actors usually focus on their own lines before going on stage, but what happened here was the product of a very different feeling.

Yes, I may have thought of Selena’s acting when I was writing the character of Mısra. Because I knew that she could successfully carry this role in line with her stage flexibility, creative energy and the performance I expected from the text. But for the character of Piraye, there was no connection with Dilek because we had not even met.

However, I can clearly state this: For a play to be successful, all the right things need to come together. The fact that Mısra was played by Selena and Piraye was played by Dilek, and that “whole” feeling was established with the lighting, music and direction made this project special. People come to me after the play and make suggestions like, “There is a very good director, we need to combine these texts with other great names.” Of course, this can happen with other texts. But in the case of Şairler Mezarlığı, I always feel like this:

“The person who knows me best had to stage it.”

The fact that Selena directed this play was a great advantage in terms of accurately reflecting the spirit of the text. Because sometimes, when I was writing the text, I didn’t focus on it much, but when I was staging it, Selena emphasizes it so much that even I admire the sentence I wrote all over again.

When you write, you are filled with emotion, you complete the text under the influence of that emotion and then you move on to another text. You don’t go back and read the same text over and over again. But when Selena reads that text, she knows me, so she can feel what thought was behind it.

This was the case with Poets’ Cemetery:

All the truths came together and the play came to life because of it.

The visual metaphors in the play are also very impressive. The cradle, shadow, silence, memorizing the poetic text… How did these come about in your mind? Did you have difficulty memorizing the text?

Selena Demirli:

I guess I am a bit lucky in this regard. My memorization power may come from my literary background. When I was studying at the Turkish Language and Literature Department of Istanbul University, we had to read, analyze, examine and even annotate very heavy texts over and over again. During this process, during the midterm and final periods, we had to memorize many texts almost involuntarily. Thanks to a habit and mental training that came from that period, I feel quite comfortable with memorization.

I don’t know if memorization is a matter of talent, but I can say that in terms of Poets’ Cemetery, it was one of the easiest texts for me to memorize. Because it has a poetic language and poetry is a genre that I love very much. Since I know Ersin’s language and inner world very well, I was able to quickly grasp the rhythm and layers of meaning of the text. However, this comfort is a personal situation. The process was more difficult for Dilek because she was out of town at that time.

Ersin Doğan:

Yes, Dilek really put up a great fight. She would send us photos showing her working with floodlights on her head all night long. He was so devoted to the text that he did not change or reduce a single sentence. From time to time he would tease me: “You made us lose our lives!” he would say, especially during the conversations with the audience after the play. But all these difficulties left us all with a sweet smile at the end because we knew that this effort was very important on the path to success.

Selena Demirli:

We also had certain rituals during the rehearsals of the play. For example, the day we were able to play a full flow from beginning to end without interruption was considered a great gain for us. Because this text is completed not only by memorization; but by correctly understanding, sensing the depth of the words and the chosen emphasis falling into place. Memorization was a step, but the real issue was “deciphering” correctly. It was necessary to hear each word correctly and at the same time convey the emotion. This was something that settled down over time.

Even now, when the day of the play comes, we usually start the memorization rehearsals at 16:00 and finish around 18:00. Especially after the seventh scene in the second half of the play, where the conflict grows, the text becomes very intense. Staging poetic texts like a “poet duel” requires not only verbal but also physical and rhythmic coordination. Voice-breath harmony, movements combined with choreography on stage, all of these have to flow like a single breath.

In this respect, the Poets’ Cemetery has improved us both physically and mentally. I can now look at the projects in front of me with a completely different eye. After experiencing such an intense, formal, language-focused and physical process, I think other texts will be more accessible. It was tiring, but it was also a very satisfying process.

We have come to the end of the season and we are at a point where we can say “oh”. We really took a breath of life. We are now entering a period where we can enjoy this process even more. I hope we continue this pleasure even more next season.

You seem to establish a secret bond with the audience in the play. How do you achieve this?

Selena Demirli:

This is definitely based on belief. From the very beginning, we believed wholeheartedly in what we were doing. We tried to make our own truths consistent. While carrying this text to the stage, we internalized its internal structure and the world it presented.

In other words, we embarked on a journey saying, “We believe in this, therefore the audience will believe in it too.”

For example, Zafer Bey specifically chose purple for the costume of the character Mısra. This reflected her existence in the womb, her abstractness and spiritual depth. A pure white costume was deemed appropriate for Piraye. Because she was the only character who belonged to this world. She had a more humane, more concrete and more painful existence. Even the tones of the characters representing the disease were turned towards green. Even these colors were a part of our belief on stage.

We really believed in Mısra’s existence in the womb, the tiny baby Piraye had to leave behind and the dilemmas the character experienced, her existential entrapment. So much so that even in a hand gesture—for example, in the gesture I used to ask Piraye, “What happened?”—there was not only a physical but also an emotional fullness. I fill that gesture with two meanings: both an indescribable curiosity and a soul’s search for existence that continues despite death.

Since we approached it with this deep belief, every moment was full of meaning for us. We knew the reason for every silence. We filled every word, every pause with meaning. I think this belief is passed on to the audience. Because no matter what we do on stage, we do it sincerely. The audience also feels this and establishes a connection.

This connection is also a connection established through impartiality. There is something I always say to Ersin: “No one should be right in the play.” Because this is a conflict text, yes—but both sides are right. One is right from a very human place, the other maybe from a superhuman place, but he is also very right. I don’t want to give away any spoilers, but the conflict experienced in the play is the encounter of two different truths. And finally, the characters understand each other, even touch each other. This touch is a result of belief and bond.

The audience believes in the world we create on stage because they internalize this feeling.

Ersin Doğan:

I think this is not specific to theater; no matter what job you do in the world, the work produced by believers and non-believers is very easy to distinguish. But the area where this difference is most clearly seen is definitely theater.

We watch a lot of plays. Sometimes the text may be mediocre, the actor may not be happy with the text. But when he goes on stage, he embraces that text in such a way, he tells it with such belief… It makes the audience feel as if it is the most important text in the world.

And the audience is affected by this belief. The actor’s stance on stage, the meaning he gives to the words, his commitment to the text are directly reflected.

Therefore, in my opinion, the most important thing is belief. We really believed in this play. This belief touched the hearts of the audience and allowed us to establish that invisible connection.

What do you want the audience to have in their hearts or minds when they leave the play?

Ersin Doğan:

For me, the most important thing is that the audience feels this way when they leave the play:

“I have to watch this play again.”

I always like plays like this. When I watch them, I ask myself: “Did I miss anything? Let this text steep in my mind for a while, then I’ll come back and look at it again.”

I think The Poets’ Cemetery should also create this feeling. Because there are so many layers, so many conflicts and different levels of emotion in it… A viewer may not be able to see them all at once. That’s why I find it very important that the play offers a structure that deserves to be watched again.

That’s what I expect from theater. There are many plays that I have watched with admiration for the second or third time today, and this play may be one of them.

In addition, there is something I say at the core of the play:

“To hurl poems at the struggle of man with man.”

I want the audience to make an assessment of their own inner world. The play’s greatest gain is for them to enter a process of questioning, which we call “pushing themselves into trouble.” Because in this text, human and non-human emotions are also in a struggle.

I want the audience to ask questions like, “Which ones do I have? Which ones are missing? What would I do if I were you?” Let them re-evaluate themselves in terms of their family, their children, and the relationships in their lives.

Let them give a struggle that belongs to this world in their inner world. I think that’s the real issue.

Selena Demirli:

It’s the same for me. As she said, Ersin has a problem. A literary, human and existential problem…

But this time from a different place: The pain of not being able to exist.

The pain of existence is usually dealt with a lot on the theater stage. But here, perhaps for the first time, we have addressed the pain of “not being able to exist.”

In other words, a being that lived only seven months before being born and died… A soul…

And this soul is trying to tell us something on stage.

However, a woman who is molded by life and the struggle to exist appears before him on stage. Therefore, a soul that has not existed and a body that has existed too much in life but is wounded come face to face.

This clash is very special in itself.

Yes, this play may not appeal to everyone at the same time. But I would also like the academic aspects of the play to be examined.

I had studied Heiner Müller during my master’s degree. Müller is a writer who re-established the language in theater.

In my opinion, the language of this play is also a language that goes beyond the ordinary and breaks the rules.

It is woven with surrealist and symbolic elements. The direction, the form, the text structure… They all create an interdisciplinary area.

I think we should also make watching plays a bit more academic.

Of course, having a good time in the theater, having fun, and being motivated are very valuable.

But at the same time, it is also very valuable to raise a theater audience that questions, investigates, gets out of its comfort zone and moves towards new areas.

I had researched the ways Heiner Müller broke the conventional structure. I feel like I found those traces again in this play.

Therefore, The Poets’ Cemetery opens up a field of research for the audience not only emotionally but also on a textual and formal level.

Even the questions you asked us—where we position the genre of poetry, how the visual elements come together—actually show that we have achieved our goal.

In other words, it is a great pleasure for me that this play arouses such a desire to question in the audience.

As a result, I want the audience to have a theater experience that touches both their heart and mind.

As Ersin said: let them question themselves, their lives, their relationships.

But at the same time, where this text stands formally in Turkish theater, what it says, what it redefines… I would also like these to be considered.

In this sense, I feel that we have been able to establish a common field of thought and emotion with the audience.

Ersin Doğan:

We actually encountered a reflection of this. Before our last play, while the audience was taking their places in the hall, we overheard some conversations.

A member of the audience was saying the following to his friend:

“There were mutual conflicts over poems in this play. It was an experimental theater.”

This was a beautiful response that warmed our hearts and showed us that we had reached the point Selena had just mentioned.

What’s the most interesting or memorable audience reaction you’ve ever received?

Selena Demirli:

The character of Mısra is a character that is very difficult to empathize with the audience. After all, she represents a soul that has died before coming to the world. Therefore, it is not easy for every audience to connect with her. However, despite this, there were a few audience reactions that came with very intense emotions, and I can never forget them.

For example, a woman who lost her baby at a very young age, or a viewer who lost a baby relative, or a woman who was pregnant and wanted to be a mother very much… One of them really affected me. A pregnant viewer who came to our play. She was an acquaintance of our production assistant, she bought a ticket without telling and came with her husband. Her belly was now very visible, she was a 7-8 month old baby.

She came and said the following after the play:

“I can’t believe how I came across this. I came here without knowing the subject of the play, but this encounter was very different and very deep for me.”

She was very emotional, she even cried.

“I am going to be a new mother and this play had such scenes about motherhood that I can’t explain,” she said.

Especially the motherhood of the character Piraye and the inability of the character Mısra to say “mother” deeply affected me. Mısra says “Mother woman” on stage because she has never had a real mother figure in her life.

In that scene where she says “I was only given a breast once, I could only touch it with my lips once”… She speaks from such a pure, such a fragile place…

For this reason, while preparing the play, I even researched the lip movements of babies in detail. I especially thought about the shapes that babies’ lips take when they are breastfeeding, how I could reflect that physical expression on stage. It was a very special and unforgettable experience for me that a play that is watched with such an emotional connection was found so meaningful by a mother-to-be.

Ersin Doğan:

I usually go to every play, but I do not take an active position during the viewing. In other words, I do not interact directly with the audience or on stage. However, I have the opportunity to have short conversations with the audience after the play. Especially the audience who come to look at the cast or creative team want to chat with me after the play.

The question I get asked most often is:

“How did you think of such a subject? Where did it come from?”

This question is asked in the everyday, sincere language of the people, and I really like that.

Encountering such questions at the end of a play shows that we are doing something really different and that this difference is felt by the audience. This feeling makes me very happy as a writer.

Will Poets’ Cemetery continue in the new season and will you have new projects as A.H.E.N.K Theater?

Selena Demirli:

Yes, Poets’ Cemetery will definitely continue in the new season. Because to be frank, it is really hard to do independent theater, especially financially. This season has been a serious economic struggle for us.

I respect the difficulties experienced by independent theater stages with all my heart. Because running a theater business requires great effort and dedication. The same goes for stage rents, technical expenses and all the processes of production.

Despite all these difficulties, we continue this work stubbornly and passionately. Because we wholeheartedly believe in what we are putting forward.

This season has exhausted us both financially and spiritually, but it has also taught us a lot. We are experienced now. We know much better which stages we can exist in, which audience profiles we connect with, and where and how we find a response.

That’s why I believe that next season, having shaken off this “amateur dust” a bit, we will continue with firmer steps and with more enjoyment.

The positive feedback we receive, the emotions we see in the audience’s eyes after the scene… All of these give us strength and say “it must continue”. So, yes, the Poets’ Cemetery will be with us in the second season as well.

Ersin Doğan:

The question of a new project always comes up, but I approach it from a slightly different perspective. I had a conversation with a young theater friend the other day. He said, “Everyone asks, what are you going to do next year?”

And I told him:

“Don’t let these questions make you feel pressured. Of course, it’s nice to produce something new, but it’s more valuable to produce a truly meaningful project, not just for the sake of it.”

We went through a long preparation process of 5-6 months for the Poets’ Cemetery. This process was not easy, it was very difficult. Then we put it on stage, and we are still going through a difficult but satisfying process with rehearsals, staging, and meeting with the audience.

This play must continue. Maybe 3 seasons, maybe more… I hope it will have a long life.

There may not be a new play in the new season within A.H.E.N.K Theater. But another text of mine may be staged by another theater. This could be a different excitement for me.

Selena can direct this new project, take on project consultancy, and work with other actors. However, after an ambitious work like Poets’ Cemetery, which A.H.E.N.K Theater signed, we do not want to start a new project just “to do something new.”

We want to appear before the audience with a work that will leave a strong impact when staged again.

Selena Demirli:

You can think of it this way: Growing this play is like raising a child.

A child is born, and then each period requires separate effort and attention. We have worked very hard this season to bring our play to the stage, to make it heard, and to bring it together with the audience.

But in the second season, this “child” is starting to grow. Maybe he will start walking. Maybe it will be staged in different cities of Türkiye and participate in festivals. It will reach more people.

We can of course enrich this journey with a new project in the future, but the “first child” always remains very special. His development, growth, dressing up in different clothes, creating himself in new playgrounds… This is the process we are going through right now.

Şairler Mezarlığı is a play that is currently 6-7 months old. It will be one year old next season and we will continue to follow and support its development.

Ersin Doğan:

Ultimately, we should not forget this: We are not a large production theater.

We were aware of this when we set out, but we saw the difficulties much more clearly in the process. Renting a stage, running the production, meeting the audience… All of these require serious effort and sacrifice.

Sometimes you have money but you still cannot cope with the structural difficulties of the sector.

We fought all these struggles this season and thankfully we ended the season well.

We hope to be back with you again in two years with a new project and a new story.

What would you like to say to our viewers and readers who love you and who will be meeting you for the first time?

Selena Demirli:

Of course. First of all, thank you very much. If they have taken the time to read this interview so far, we would like to thank the valuable viewers and followers of Oiktoz and especially you, Ms. Bilge, from the bottom of our hearts.

I am also grateful for the invitation to the interview and the depth of your questions. Your viewing of the play, the evaluation texts you wrote, your writings… They are all very valuable to us. We read those lines written by you and shared them on our social media posts, especially mentioning your name. It made us very happy.

I think you are doing something very valuable. I would also like to thank Oiktoz for its existence in terms of increasing the number of such platforms, supporting production and creativity, and increasing the visibility of independent theater teams.

Your greatest contribution is to continue to go to the theater as an audience and to support independent teams.

It is a good thing you exist. Really… It is a good thing you exist.

Ersin Doğan:

As a writer, I would like to say this:

I would like to leave a small note for everyone who follows you, reads your writings or sees this interview through you – especially for those friends who want to be writers, want to produce but don’t know what to do.

I believe that these lands are very valuable. I believe that Anatolia is one of the strongest veins of literary and artistic production.

Like Ahmet Arif’s famous words:

“I am Anatolia.”

Yes, I am a little like that too. I think the stories born from these lands can resonate all around the world.

The Poets’ Cemetery emerged with this perspective. My dream is for this play to be staged in a different language, in a different country one day.

I live with this dream and continue to write with this dream.

I would like to say the same thing to everyone who wants to write:

Never give up on dreaming. But they shouldn’t just dream, they should follow that dream themselves.

Because no one sets out to realize someone else’s dream. If you don’t stand up for your dream, no one else will.

People who leave their mark on history usually exist through their own struggles. People who are “brought somewhere” by others usually don’t stay there for long. And then, we realize that they are lost in the dark pages of history.

Let this be just a little advice. Because I still continue that struggle.

I still have a hard time saying “I am a writer” even to myself. I say more like this:

“I am someone who wants to be a writer.”

Let me also address those who will meet us for the first time with this message.

We thank you very much again.

You came to our game, you became our voice, you became our breath.

We hope that in future projects, we will take part in your projects and you in ours…

Hoping to meet again in new stories.

___

oiktoz interviews – Poets’ Cemetery: In Türkiye, Poets Don’t Have Books, They Only Have Cemeteries

___

TEAM

Poets’ Cemetery Actors

Dilek Uluer

Selena Demirli

Poets’ Cemetery Backstage

Set Design: Zafer Metin

Photography: Yiğit Tumri

Light Operator: Eren Süloğlu

Light Design: Zafer Metin

Costume Design: Sefa Eraslan

Music: Coşkun Yaşar

Assistant Director: Cemre Naz

Production Assistant: Akif Fentçi

Writer: Ersin Doğan

Director: Selena Demirli

Assistant Director: Kübra Karatepe

Poster Design: Coşkun Yaşar